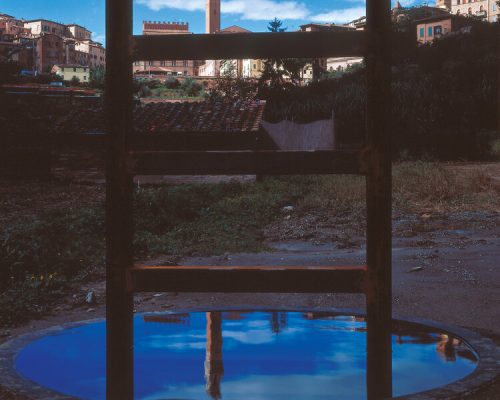

The 7th edition of Arte all'Arte, curated by Emanuela De Cecco and Vicente Todolí, brought significant interventions to the most evocative places in Tuscany. Cildo Meireles raised Siena to the sky, Miroslaw Balka left his mark in San Gimignano, Lothar Baumgarten transformed Montalcino, while Tacita Dean projected in Mensano. Marisa Merz enriched Colle di Val d’Elsa and Damián Ortega enhanced Poggibonsi.

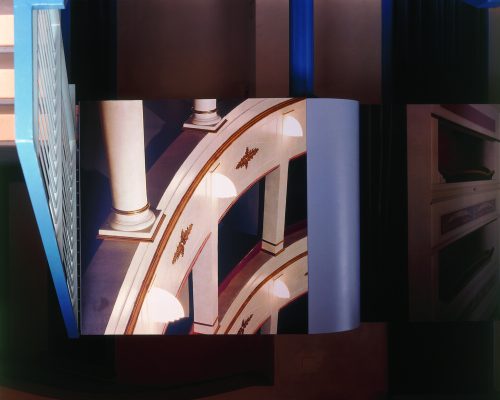

The edition also featured a special project at the Palazzo delle Papesse and an installation by Mario Airò at the Teatro dei Leggeri in San Gimignano, confirming the deep connection between contemporary art and the territory.

Edited by Emanuela de Cecco and Vicente Todoli.

"With this project, the Arte Continua association sought to create a point of contact between the world of international contemporary art and some local Tuscan communities strongly marked by the presence of art, especially medieval and Renaissance art, developing two research strands: one exploring connections between Art Architecture Landscape, and the other between Art Technology and Science.

Siamo appassionati dell’arte di ogni tempo e per noi il Medioevo, il Rinascimento e il bellissimo paesaggio toscano non sono esattamente il passato, o un’immagine da cartolina, ma una parte importante della nostra vita, del nostro presente, e ci auguriamo anche del nostro futuro.”

Art to Art è giunta alla sua settima edizione e, come ogni anno, si svolge in spazi particolarissimi, spazi che spesso hanno vissuto una vita precedente ospitando le più svariate attività di cui conservano le tracce, spazi di fatto non predisposti per accogliere l’arte contemporanea ma di volta in volta riadattati a seconda dei progetti degli artisti e delle possibilità concrete.

(…)

Every decision must be verified in light of a very concrete reality test: the project of a world-renowned artist can be supported or opposed from the perspective of a parish priest in a small village. In some cases, it is more important to have a feel for the actual situation rather than relying on potential intellectual legitimizations. I believe that what makes this experience meaningful is the ability to give form once a year to a small, focused concrete utopia through which art finds an opportunity for effective dialogue – even before with the public – with the different realities that host it.

If the way in which art is conveyed and communicated to the public has always been one of the central questions that those working around art are constantly called to address, today this issue is even more urgent.

Museums are transforming, the logic of entertainment is gaining a weight it did not have before in programming, and culture must also entertain. Art, if it intends to maintain some autonomy in this process, must keep the dialogue with reality alive, giving up on retreating into pseudo-aristocratic positions. The most interesting hypothesis is that it is possible to configure a sort of third way capable of communicating without distorting itself, without yielding to increasingly pressing populist pressures. In this context, Arte all'Arte is an experience where these questions transform into action, and from which each year an attempt is made to offer an overview of possible concrete attempts at answers.

Moreover, the trust in the act of doing invalidates some of the most common complaints about issues related to the difficult survival of contemporary art in a country that is still incredibly frightened by artistic production not attributable – for demographic reasons – to the heritage of cultural assets. In the face of more than one mayor willing to engage directly and confront the project of an artist, the immobility of the large cities appears even stronger, where bureaucracy and the accumulation of broken promises neutralize tons of energy.

In this context, the response arises precisely during the preparation of the exhibition and takes shape through the network of relationships – built over the years but reviewed and deepened every year – that forms between local administrations, the people responsible for the places where the works are set up, the artists themselves, the curators, the organizers, the artisans, and the technicians. Even at this stage, one is already confronted with the life of the territory, with the concrete resources, fears, and forms of resistance. Already in the design phase, there exists a sort of primary audience whose involvement is required, transforming into a precise responsibility that can be of vital importance regarding the realization of a specific intervention or the need to change direction and start over in another way.

Even before the actual visitors' audience, everyone's work must pass this sort of initial field test, which is perhaps one of the most interesting phases precisely in relation to that need for reality testing I mentioned earlier.

(…)

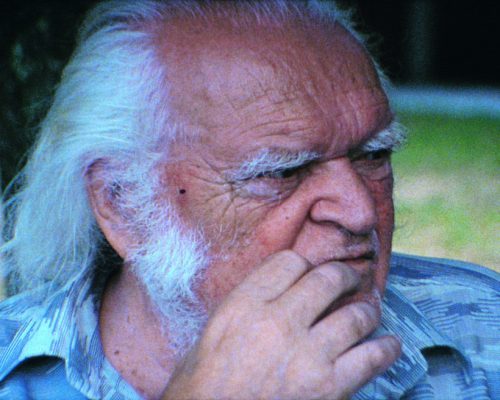

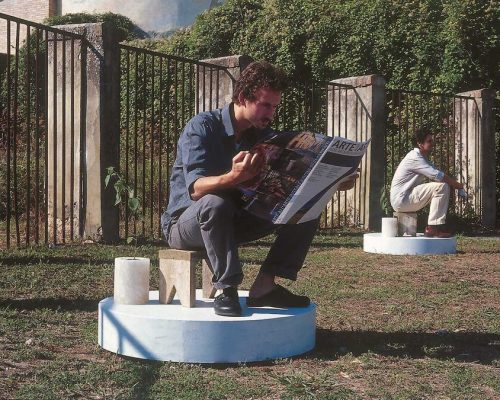

I don't think it's a coincidence that the reflection on time is present in the work of more than one artist. I think of the always equal time marked by the platforms with seating by Balka in the spaces of the former prison in San Gimignano, and the time of rest and daily life, which I believe is the true subtext of the film Mario Merz by Tacita Dean, projected in the small cinema of the Mensano club.

In times of frantic rush toward increasingly unclear objectives, the red thread that emerges from multiple contributions lies in the need for a rethinking, in relating to the public not by trying to amaze but by privileging the dimension of listening, not being afraid to take a step into the darkness and depth (Marisa Merz, Cildo Meireles, Miroslaw Balka), welcoming and valuing differences (Damián Ortega), looking at the territory rather than consuming it (Baumgarten), considering the traces of the existing, as in the drawings of Tacita Dean where the profiles of maps follow the veins of the alabaster itself...

Emanuela De Cecco, da Arte all’Arte VII