Interview by Jérôme Sans and Pier Luigi Tazzi

What is your work about?

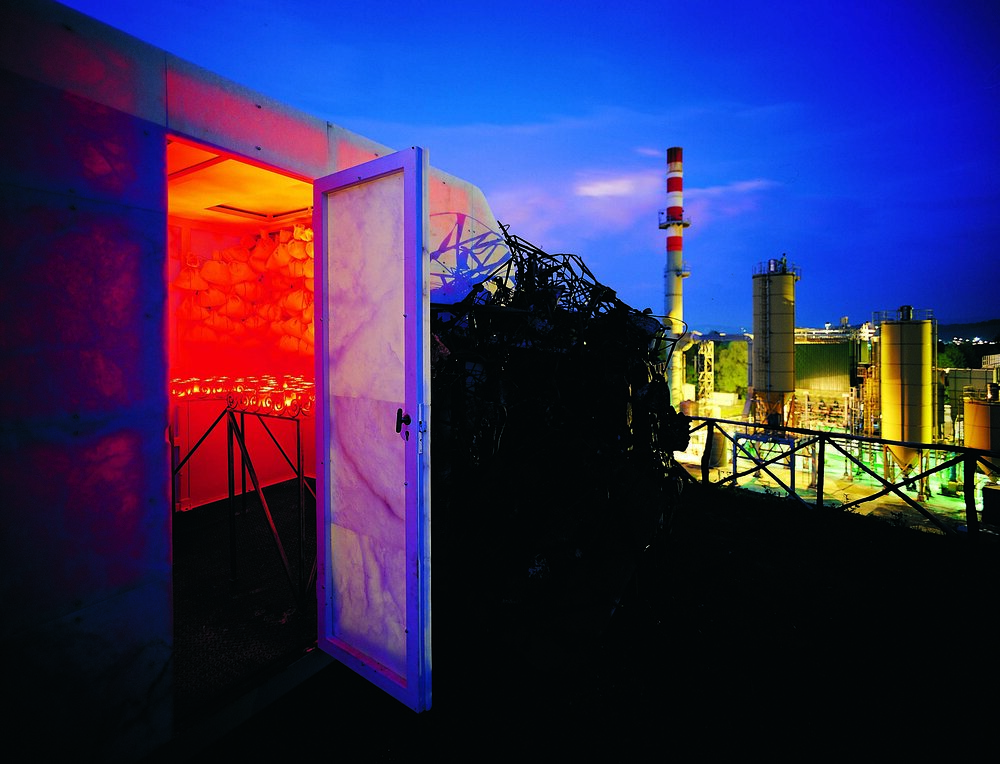

It is a caravan made of alabaster that seems to have gotten stuck in a pile of debris. Inside the caravan, there are stools made from tires, a small table full of candles, and bags filled with corn, wheat, and oats. I chose to work with a caravan because caravans are one of the main products of Poggibonsi. Why did I choose Poggibonsi? Because it is an industrial city that was almost completely destroyed during World War II. It is truly ironic that their main industry produces mobile homes. The site of the work is a small hill adjacent to the incinerator, a space chosen because it has an untold history. The hill-landfill is made up of accumulated and buried material that decomposes and returns to nature. It is a very ordinary process, concentrated and made systematic. I want the incinerator to be a place of dialogue for my work. To raise issues related to morality, mortality, and responsibility, that's why I used the unwanted history of the place, which is garbage, and the metaphor of the sanctuary as a place of encounter.

The choice of location is very interesting because you propose a Tuscan scenario behind the scenes, a truly real and contemporary hidden part. It’s somewhat similar to the Centre Pompidou. But in this place, what hasn’t been conceived as a stage?

This is a place that people try to deny, but it is a place that is significant for many reasons. I think it is very important to bring things to light to allow people to reflect on their own lives. And this idea of light is fundamental to the work, and I refer to the light of the incinerator’s fire, the light of the sun, and the light of the candles inside the sanctuary.

Debris has always been a central material in your work, but you’ve never combined waste with a precious material like alabaster. How do you see this change?

Alabaster is a material that has a lot to do with light, it diffuses light, and it’s this alteration that interests me because it creates a truly special atmosphere. It is very important to find a balance between the darkness and the seemingly negative connotation of the incinerator’s residues on one side, and on the other, a brighter and more contemplative space.

Does the use of candles and alabaster not carry a funeral connotation, especially when combined with an incinerator?

Esattamente per questo che ho voluto che la mia opera avesse la forma di un caravan. Come anche tu dici il caravan rimanda al concetto di piacere e di svago, alla transitorietà. Cosi il concetto di movimento è fondamentale per quest’opera, anche a livello visivo; una forma che si muove in un’altra, attraverso riferimenti analoghi rafforza l’idea di trasformazione.

Alabaster is used to make figurines and other kitsch objects: now, even turning it into a caravan, isn’t that process akin to kitsch?

I agree. I don’t find it kitsch, but rather playful. And like a big toy, I like this idea because it frees it from the gravity of death. Working with the incinerator staff was an extraordinary experience that allowed me to witness a powerful transformation using fire, which, despite being part of this industrial-scale process, still maintains a certain intimacy with the material. In other words, the incinerator is a machine that erases, but leaves traces of recognition.

What is your relationship with "bricolage" and especially with that of African Americans? Isn’t the art of bricolage still the art of slaves?

For me, bricolage is taking a material and giving it a function it doesn’t normally have. It’s a very intelligent process because it involves a very high level of invention. I enjoy the challenge of changing someone’s expectations by surprising them with new combinations.

Arte all’Arte VI, 2001