Elsa

"Jimmie Durham is a Cherokee, born in Arkansas (USA) in 1940. He is a visual artist, but also an essayist and political activist with the American Indian Movement. Devoted more to theater and performance in the 1960s and ’70s, since the ’80s he has also created strange objects, assemblages, and installations that draw heavily from his own culture, which he uses to deconstruct stereotypes and prejudices of Western culture.

For this reason, he has already been recognized as one of the leading figures in the international movement inspired by anthropology and postcolonial themes, and he has participated in various international exhibitions such as Documenta IX in 1992 and the 50th Venice Biennale.

Ironic and sharp-witted, his work responds—through the reuse of materials—to the skepticism of Western culture toward different beliefs and ways of life: a plastic pipe or a stick is not a snake, but it can serve the same function. Humanity is certainly a part of nature, which includes everything. But postmodernly, the artificiality of certain materials integrated into his objects, the flirtation with the kitsch stereotype of Native Americans and their culture, the very history of the assemblage form, and the reference to “primitivism” in 20th-century art—are these not signs of the irony with which Durham also looks at himself? And doesn’t he thus reverse the perspective, offering a vision for the future instead of an impossible search for roots too deeply buried by time?

For Arte all’Arte, Durham created the sculpture of the spirit of the Elsa River, using various materials and a technique meant to evoke the tradition of ancient wooden saints, similar to prehistoric figures. The spirit, with long Gorgon-like hair and a large hammer in one hand, emerges at the end of a long “snake” whose body is made from industrial PVC piping, rising up and stretching over the waters of the river and, like the river, progressively widening.

What is a spirit? What is a river?

Museum of Paper

The Museum is not only a place for the consecration and display of historical objects, documents, and images. Its primary function is to legitimize knowledge through its activities of collecting, selecting, cataloguing, and presenting objects, texts, images, etc. This process tends to demonstrate the authenticity of historical materials, but it is by no means a purely intellectual process; on the contrary, it directly and indirectly represents specific ideologies and historical conditions, legitimizing the dominance of a given political and cultural power.

Artistic work and intellectual engagement have systematically focused on the global hegemony of today's Western knowledge system, or the "authentic" order of things. The museum represents this hegemony in its most perfect form, while generally being considered the ultimate space for artistic consecration.

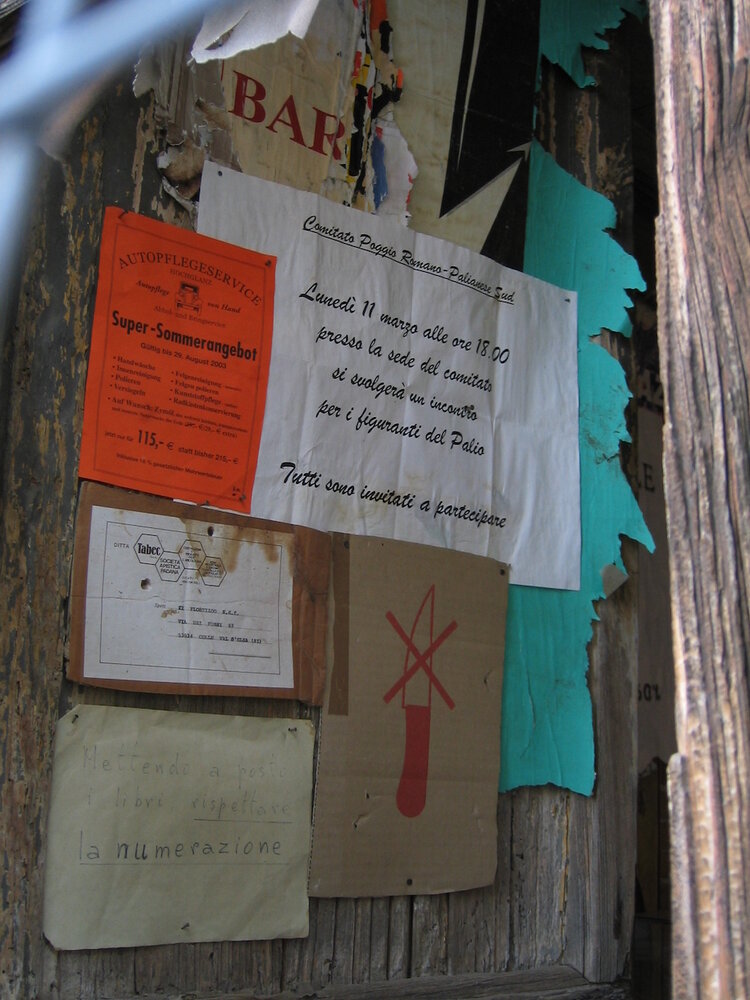

Deeply struck by an abandoned paper mill in Colle di Val d’Elsa, Jimmie Durham decided to transform it into his own Museum of Paper, collecting every type of paper—from schoolbooks to wallpaper, from torn posters and notes, to artworks and garbage. Durham created a totally chaotic representation of paper, the exact embodiment of “civilization.”

This collection of scraps, in turn, subverts the essential order of hegemonic power embodied by the modern cultural Museum itself. At the same time, this critique gives rise to an aesthetic dynamism marked by irony, humor, poetry, and lightness."

Art to Art VIII, 2002