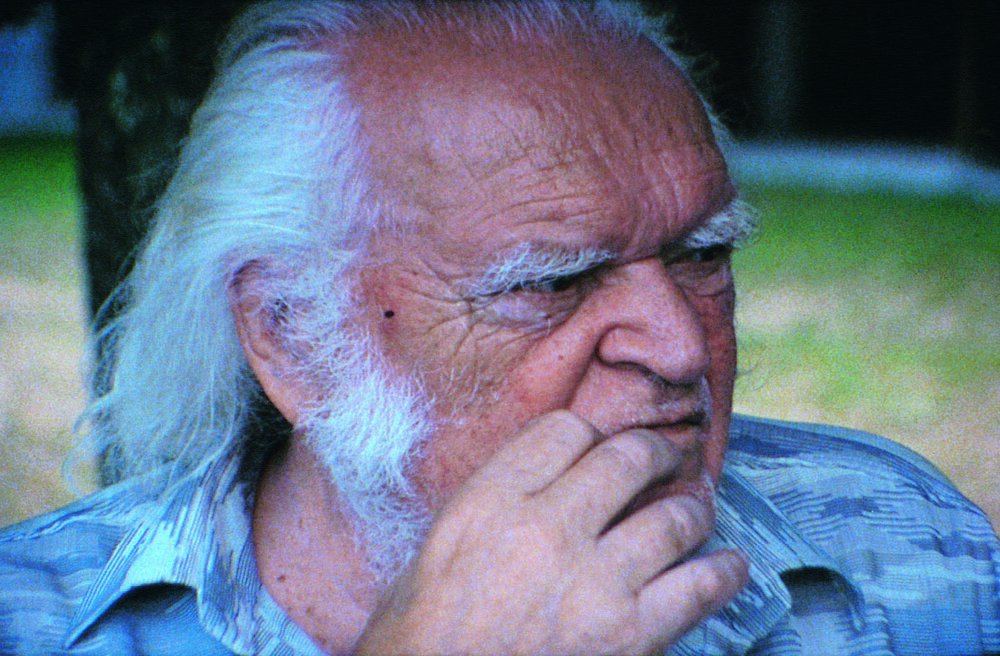

“Avevo già incontrato Mario tre volte prima di quest’estate a San Gimignano. La prima volta era stata a Bologna, lo avevo visto, osservato, e alla fine, dopo cena, mi ero avvicinata e gli avevo detto che era identico a mio padre. Mi aveva baciato la mano e se ne era andato. Dopo questo incontro ho perseguitato la fotografa ufficiale del museo per avere una sua foto; mi ha promesso che me l’avrebbe mandata, ma poi non l’ha fatto. Volevo affiancare le immagini dei due uomini per documentare la somiglianza a riprova della mia obiettività. L’ho rivisto a Parigi, mi sono imbattuta con lui e Marisa che facevano colazione in Place des Vosges. E poi ancora alla Biennale di Venezia dove ho tentato spudoratamente di fotografarlo con una macchina in prestito prima che si scaricasse la pila e tornasse il legittimo proprietario. Per questo a San Gimignano, quando sono entrata in quel giardino e ho visto Mario a capotavola che pranzava sotto gli alberi, ho sentito l’impulso irrefrenabile di riprendere a scrutarlo. Quando sono tornata la volta seguente ho portato con me la cinepresa. Per una settimana mi hanno accompagnata in giro alla ricerca di un soggetto per il mio progetto, ma non sono giunta a niente. E ogni sera cenavamo tutti insieme intorno al tavolo, sotto gli alberi, e potevo osservare il mio vero – e apparentemente irraggiungibile – oggetto del desiderio. L’ultimo giorno non avevo scelta, dovevo provarci. Dopo un gelato cioccolato e frutti di bosco gli ho detto: “Mario posso girare?” “Va bene” ha risposto “Ma senza parlare”. Così quel pomeriggio in giardino, al tavolo sotto gli alberi, abbiamo girato il film. Mario ha raccolto una grossa pigna e se l’è messa in grembo. Mentre Mario chiacchierava il sole andava e veniva a scatti con estemporanei e maldestri effetti di luce e ombra, dalla piazza principale arrivava il rintocco funebre delle campane, le cicale frinivano interrompendosi e riprendendo a loro piacimento e i corvi volavano avanti e indietro dal tetto. Ha cambiato varie sedie e postazioni nel giardino, e sono riuscita a girare quattro bobine prima che il sole fosse offuscato da nubi minacciose e scoppiasse il temporale. Ma è successo dell’altro. All’improvviso non riconoscevo più i lineamenti di mio padre nel volto di Mario, né nei movimenti delle mani o nel modo di camminare a piccoli passi. Sembrava che l’origine stessa del mio desiderio si fosse autodistrutta e che girando il film mi fossi purificata dalla mia soggettività. Alla fine Mario Merz era diventato per me Mario Merz. Era come se l’ingannevole somiglianza con mio padre non fosse stata altro che il mezzo per farmi girare un film di Mario in giardino quel pomeriggio a San Gimignano. E la somiglianza impressionante e inquietante con mio padre ormai riuscivo a malapena a vederla.”

— Tacita Dean, Arte all’Arte VII, 2002